You probably take steps to maintain your physical health, but you may not know that you can also take steps to improve your brain and maintain its health. Promising new research suggests that a number of things that are good for our overall physical health are especially important for the health of our brain. Based on these findings, five things you can do for your brain are:

1. Eat less meat.

2. Lift weights at least two times a week.

3. Include foods with probiotics in your diet.

4. Get regular aerobic exercise.

5. Don’t skimp on sleep.

Here are links to articles reporting the results of the studies. Click on the titles to read the full stories.

1. Could A Mediterranean Diet Keep Your Brain From Shrinking?

Previous research has connected a Mediterranean diet to a reduced risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease and other degenerative brain conditions. In a recent study, researchers focused on elderly people with normal cognitive function to see if the diet might also be tied to losing fewer brain cells due to aging.

“Among cognitively healthy older adults, we were able to detect an association between higher adherence to a Mediterranean type diet and better brain measures,” according to lead study author Yian Gu of Columbia University in New York.

Higher fish intake and lower meat consumption, one aspect of a Mediterranean diet, was tied to larger total gray matter volume on the brain scans.

Eating less meat was also independently associated with larger total brain volume.

Overall, the difference in brain volume between the people who followed a Mediterranean diet and those who didn’t was similar to the effect of five years of aging, the researchers conclude in the journal Neurology.

2. Lifting Weights, Twice a Week, May Aid the Brain

Most studies of exercise and brain health have focused on the effects of running, walking or other aerobic activities. A few encouraging past studies have suggested that regular, moderate aerobic exercise such as walking may slow the progression of white matter lesions in older people.

But Teresa Liu-Ambrose, a professor of physical therapy and director of the Aging, Mobility, and Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, wondered whether other types of exercise would likewise be beneficial for white matter. In particular, she was interested in weight training, because weight training strengthens and builds muscles.

After a year-long study, women aged 65-75 who had lifted weights twice per week displayed significantly less shrinkage and tattering of their white matter than the other women. Their lesions had grown and multiplied somewhat, but not nearly as much. They also walked more quickly and smoothly than the women in the other two groups.

Note that the result was only achieved in the group who lifted weights twice per week, not in a group who lifted only once a week.

3. Probiotics on the Brain

A growing number of scientists now believe that gut bacterial can influence mental health.

The idea that microbes in the body can affect the brain has gone in and out of fashion. In 1896, physicians writing in Scientific American concluded, in the language of the day, that “certain forms of insanity” could be caused by infectious agents “similar to typhoid, diphtheria and others.” But after Freudian psychoanalysis became popular in the first half of the 20th century, the microbial theory of mental illness was largely forgotten, and stayed that way for decades.

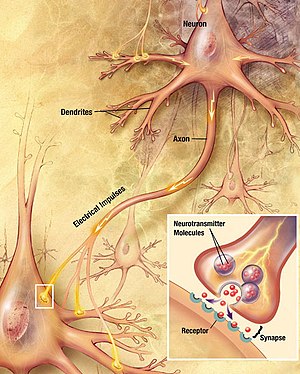

Today, however, scientists know that trillions of micro-organisms live in your digestive system, where they outnumber your human cells many times over and may make up as much as 3 percent of your body weight. The evidence that these bacteria affect a dense network of neurons in your gut — often called the “second brain”— is vast and growing.

It’s unclear exactly how or which bacteria cause or cure which disorders and in what complex ways, Dr. James Greenblatt, a psychiatrist and the chief medical officer of Walden Behavioral Care, says, “but the research is quite clear that the GI tract affects brain health.” In this case, he says, “one plus one does equal two.”

4. Regular Exercise Changes the Brain to Improve Memory, Thinking Skills

In a study done at the University of British Columbia, researchers found that regular aerobic exercise, the kind that gets your heart and your sweat glands pumping, appears to boost the size of the hippocampus, the brain area involved in verbal memory and learning. Resistance training, balance and muscle toning exercises did not have the same results.

Many studies have suggested that the parts of the brain that control thinking and memory (the prefrontal cortex and medial temporal cortex) have greater volume in people who exercise versus people who don’t. “Even more exciting is the finding that engaging in a program of regular exercise of moderate intensity over six months or a year is associated with an increase in the volume of selected brain regions,” says Dr. Scott McGinnis, a neurologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an instructor in neurology at Harvard Medical School.

How much exercise is required? The study participants walked briskly for one hour, twice a week. That’s 120 minutes of moderate intensity exercise a week. Standard recommendations advise half an hour of moderate physical activity most days of the week, or 150 minutes a week. If that seems daunting, start with a few minutes a day, and increase the amount you exercise by five or 10 minutes every week until you reach your goal.

If you don’t want to walk, consider other moderate-intensity exercises, such as swimming, stair climbing, tennis, squash, or dancing. Don’t forget that household activities can count as well, such as intense floor mopping, raking leaves, or anything that gets your heart pumping so much that you break out in a light sweat.

5. Good Night. Sleep Clean.

Sleep, it turns out, may play a crucial role in our brain’s physiological maintenance. As your body sleeps, your brain is quite actively playing the part of mental janitor: It’s clearing out all of the junk that has accumulated as a result of your daily thinking.

Recall what happens to your body during exercise. You start off full of energy, but soon enough your breathing turns uneven, your muscles tire, and your stamina runs its course. What’s happening internally is that your body isn’t able to deliver oxygen quickly enough to each muscle that needs it and instead creates needed energy anaerobically. And while that process allows you to keep on going, aside effect is the accumulation of toxic byproducts in your muscle cells. Those byproducts are cleared out by the body’s lymphatic system, allowing you to resume normal function without any permanent damage.

The lymphatic system serves as the body’s custodian: Whenever waste is formed, it sweeps it clean. The brain, however, is outside its reach — despite the fact that your brain uses up about 20 percent of your body’s energy. How, then, does its waste — like beta-amyloid, a protein associated with Alzheimer’s disease — get cleared? What happens to all the wrappers and leftovers that litter the room after any mental workout?

“Think about a fish tank,” says Dr. Nedergaard. “If you have a tank and no filter, the fish will eventually die. So, how do the brain cells get rid of their waste? Where is their filter?”

Until a few years ago, the prevailing model was based on recycling: The brain got rid of its own waste, not only beta-amyloid but other metabolites, by breaking it down and recycling it at an individual cell level. When that process eventually failed, the buildup would result in age-related cognitive decline and diseases like Alzheimer’s. That “didn’t make sense” to Dr. Nedergaard, who says that “the brain is too busy to recycle” all of its energy. Instead, she proposed a brain equivalent of the lymphatic system, a network of channels that cleared out toxins with watery cerebrospinal fluid. She called it the glymphatic system, a nod to its dependence on glial cells (the supportive cells in the brain that work largely to maintain homeostasis and protect neurons) and its function as a sort of parallel lymphatic system.

So far the glymphatic system has been identified as the neural housekeeper in baboons, dogs and goats. “If anything,” Dr. Nedergaard says, “it’s more needed in a bigger brain.”

Improve Your Brain–or Lose It?

It’s good news for all of us that there are things we can do to have a positive effect on our brain, from increasing its size to improving cognitive processing to (you should excuse the expression) taking out the trash. Of course, the opposite is also true. Things that we do can have a negative effect on our brain, and that’s not good. But we can’t say we haven’t been warned.